As a software developer, you certainly have a high-level picture of how web apps work and what kinds of technologies are involved: the browser, HTTP, HTML, web server, request handlers, and so on.

In this article, we will take a deeper look at the sequence of events that take place when you visit a URL.

1. You enter a URL into the browser

It all starts here:

2. The browser looks up the IP address for the domain name

The first step in the navigation is to figure out the IP address for the visited domain. The DNS lookup proceeds as follows:

- Browser cache – The browser caches DNS records for some time. Interestingly, the OS does not tell the browser the time-to-live for each DNS record, and so the browser caches them for a fixed duration (varies between browsers, 2 – 30 minutes).

- OS cache – If the browser cache does not contain the desired record, the browser makes a system call (gethostbyname in Windows). The OS has its own cache.

- Router cache – The request continues on to your router, which typically has its own DNS cache.

- ISP DNS cache – The next place checked is the cache ISP’s DNS server. With a cache, naturally.

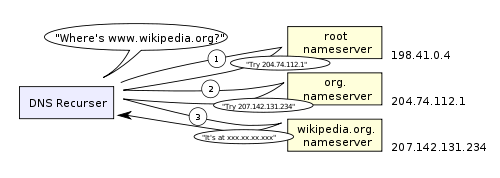

- Recursive search – Your ISP’s DNS server begins a recursive search, from the root nameserver, through the .com top-level nameserver, to Facebook’s nameserver. Normally, the DNS server will have names of the .com nameservers in cache, and so a hit to the root nameserver will not be necessary.

Here is a diagram of what a recursive DNS search looks like:

One worrying thing about DNS is that the entire domain like wikipedia.org or facebook.com seems to map to a single IP address. Fortunately, there are ways of mitigating the bottleneck:

- Round-robin DNS is a solution where the DNS lookup returns multiple IP addresses, rather than just one. For example, facebook.com actually maps to four IP addresses.

- Load-balancer is the piece of hardware that listens on a particular IP address and forwards the requests to other servers. Major sites will typically use expensive high-performance load balancers.

- Geographic DNS improves scalability by mapping a domain name to different IP addresses, depending on the client’s geographic location. This is great for hosting static content so that different servers don’t have to update shared state.

- Anycast is a routing technique where a single IP address maps to multiple physical servers. Unfortunately, anycast does not fit well with TCP and is rarely used in that scenario.

Most of the DNS servers themselves use anycast to achieve high availability and low latency of the DNS lookups.

3. The browser sends a HTTP request to the web server

You can be pretty sure that Facebook’s homepage will not be served from the browser cache because dynamic pages expire either very quickly or immediately (expiry date set to past).

So, the browser will send this request to the Facebook server:

GET http://facebook.com/ HTTP/1.1 Accept: application/x-ms-application, image/jpeg, application/xaml+xml, [...] User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; [...] Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate Connection: Keep-Alive Host: facebook.com Cookie: datr=1265876274-[...]; locale=en_US; lsd=WW[...]; c_user=2101[...]

The GET request names the URL to fetch: “http://facebook.com/”. The browser identifies itself (User-Agent header), and states what types of responses it will accept (Accept and Accept-Encoding headers). The Connection header asks the server to keep the TCP connection open for further requests.

The request also contains the cookies that the browser has for this domain. As you probably already know, cookies are key-value pairs that track the state of a web site in between different page requests. And so the cookies store the name of the logged-in user, a secret number that was assigned to the user by the server, some of user’s settings, etc. The cookies will be stored in a text file on the client, and sent to the server with every request.

There is a variety of tools that let you view the raw HTTP requests and corresponding responses. My favorite tool for viewing the raw HTTP traffic is fiddler, but there are many other tools (e.g., FireBug) These tools are a great help when optimizing a site.

In addition to GET requests, another type of requests that you may be familiar with is a POST request, typically used to submit forms. A GET request sends its parameters via the URL (e.g.: http://robozzle.com/puzzle.aspx?id=85). A POST request sends its parameters in the request body, just under the headers.

The trailing slash in the URL “http://facebook.com/” is important. In this case, the browser can safely add the slash. For URLs of the form http://example.com/folderOrFile, the browser cannot automatically add a slash, because it is not clear whether folderOrFile is a folder or a file. In such cases, the browser will visit the URL without the slash, and the server will respond with a redirect, resulting in an unnecessary roundtrip.

4. The facebook server responds with a permanent redirect

This is the response that the Facebook server sent back to the browser request:

HTTP/1.1 301 Moved Permanently

Cache-Control: private, no-store, no-cache, must-revalidate, post-check=0,

pre-check=0

Expires: Sat, 01 Jan 2000 00:00:00 GMT

Location: http://www.facebook.com/

P3P: CP="DSP LAW"

Pragma: no-cache

Set-Cookie: made_write_conn=deleted; expires=Thu, 12-Feb-2009 05:09:50 GMT;

path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Cnection: close

Date: Fri, 12 Feb 2010 05:09:51 GMT

Content-Length: 0

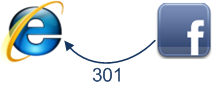

The server responded with a 301 Moved Permanently response to tell the browser to go to “http://www.facebook.com/” instead of “http://facebook.com/”.

There are interesting reasons why the server insists on the redirect instead of immediately responding with the web page that the user wants to see.

One reason has to do with search engine rankings. See, if there are two URLs for the same page, say http://www.igoro.com/ and http://igoro.com/, search engine may consider them to be two different sites, each with fewer incoming links and thus a lower ranking. Search engines understand permanent redirects (301), and will combine the incoming links from both sources into a single ranking.

Also, multiple URLs for the same content are not cache-friendly. When a piece of content has multiple names, it will potentially appear multiple times in caches.

5. The browser follows the redirect

The browser now knows that “http://www.facebook.com/” is the correct URL to go to, and so it sends out another GET request:

GET http://www.facebook.com/ HTTP/1.1 Accept: application/x-ms-application, image/jpeg, application/xaml+xml, [...] Accept-Language: en-US User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; [...] Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate Connection: Keep-Alive Cookie: lsd=XW[...]; c_user=21[...]; x-referer=[...] Host: www.facebook.com

The meaning of the headers is the same as for the first request.

6. The server ‘handles’ the request

The server will receive the GET request, process it, and send back a response.

This may seem like a straightforward task, but in fact there is a lot of interesting stuff that happens here – even on a simple site like my blog, let alone on a massively scalable site like facebook.

- Web server software

The web server software (e.g., IIS or Apache) receives the HTTP request and decides which request handler should be executed to handle this request. A request handler is a program (in ASP.NET, PHP, Ruby, …) that reads the request and generates the HTML for the response.In the simplest case, the request handlers can be stored in a file hierarchy whose structure mirrors the URL structure, and so for example http://example.com/folder1/page1.aspx URL will map to file /httpdocs/folder1/page1.aspx. The web server software can also be configured so that URLs are manually mapped to request handlers, and so the public URL of page1.aspx could be http://example.com/folder1/page1.

- Request handler

The request handler reads the request, its parameters, and cookies. It will read and possibly update some data stored on the server. Then, the request handler will generate a HTML response.

One interesting difficulty that every dynamic website faces is how to store data. Smaller sites will often have a single SQL database to store their data, but sites that store a large amount of data and/or have many visitors have to find a way to split the database across multiple machines. Solutions include sharding (splitting up a table across multiple databases based on the primary key), replication, and usage of simplified databases with weakened consistency semantics.

One technique to keep data updates cheap is to defer some of the work to a batch job. For example, Facebook has to update the newsfeed in a timely fashion, but the data backing the “People you may know” feature may only need to be updated nightly (my guess, I don’t actually know how they implement this feature). Batch job updates result in staleness of some less important data, but can make data updates much faster and simpler.

7. The server sends back a HTML response

Here is the response that the server generated and sent back:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: private, no-store, no-cache, must-revalidate, post-check=0,

pre-check=0

Expires: Sat, 01 Jan 2000 00:00:00 GMT

P3P: CP="DSP LAW"

Pragma: no-cache

Content-Encoding: gzip

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

X-Cnection: close

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Date: Fri, 12 Feb 2010 09:05:55 GMT

2b3

��������T�n�@����[...]

The entire response is 36 kB, the bulk of them in the byte blob at the end that I trimmed.

The Content-Encoding header tells the browser that the response body is compressed using the gzip algorithm. After decompressing the blob, you’ll see the HTML you’d expect:

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN"

"http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd">

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" xml:lang="en"

lang="en" id="facebook" class=" no_js">

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<meta http-equiv="Content-language" content="en" />

...

In addition to compression, headers specify whether and how to cache the page, any cookies to set (none in this response), privacy information, etc.

Notice the header that sets Content-Type to text/html. The header instructs the browser to render the response content as HTML, instead of say downloading it as a file. The browser will use the header to decide how to interpret the response, but will consider other factors as well, such as the extension of the URL.

8. The browser begins rendering the HTML

Even before the browser has received the entire HTML document, it begins rendering the website:

9. The browser sends requests for objects embedded in HTML

As the browser renders the HTML, it will notice tags that require fetching of other URLs. The browser will send a GET request to retrieve each of these files.

Here are a few URLs that my visit to facebook.com retrieved:

- Images

http://static.ak.fbcdn.net/rsrc.php/z12E0/hash/8q2anwu7.gif

http://static.ak.fbcdn.net/rsrc.php/zBS5C/hash/7hwy7at6.gif

… - CSS style sheets

http://static.ak.fbcdn.net/rsrc.php/z448Z/hash/2plh8s4n.css

http://static.ak.fbcdn.net/rsrc.php/zANE1/hash/cvtutcee.css

… - JavaScript files

http://static.ak.fbcdn.net/rsrc.php/zEMOA/hash/c8yzb6ub.js

http://static.ak.fbcdn.net/rsrc.php/z6R9L/hash/cq2lgbs8.js

…

Each of these URLs will go through process a similar to what the HTML page went through. So, the browser will look up the domain name in DNS, send a request to the URL, follow redirects, etc.

However, static files – unlike dynamic pages – allow the browser to cache them. Some of the files may be served up from cache, without contacting the server at all. The browser knows how long to cache a particular file because the response that returned the file contained an Expires header. Additionally, each response may also contain an ETag header that works like a version number – if the browser sees an ETag for a version of the file it already has, it can stop the transfer immediately.

Can you guess what “fbcdn.net” in the URLs stands for? A safe bet is that it means “Facebook content delivery network”. Facebook uses a content delivery network (CDN) to distribute static content – images, style sheets, and JavaScript files. So, the files will be copied to many machines across the globe.

Static content often represents the bulk of the bandwidth of a site, and can be easily replicated across a CDN. Often, sites will use a third-party CDN provider, instead of operating a CND themselves. For example, Facebook’s static files are hosted by Akamai, the largest CDN provider.

As a demonstration, when you try to ping static.ak.fbcdn.net, you will get a response from an akamai.net server. Also, interestingly, if you ping the URL a couple of times, may get responses from different servers, which demonstrates the load-balancing that happens behind the scenes.

10. The browser sends further asynchronous (AJAX) requests

In the spirit of Web 2.0, the client continues to communicate with the server even after the page is rendered.

For example, Facebook chat will continue to update the list of your logged in friends as they come and go. To update the list of your logged-in friends, the JavaScript executing in your browser has to send an asynchronous request to the server. The asynchronous request is a programmatically constructed GET or POST request that goes to a special URL. In the Facebook example, the client sends a POST request to http://www.facebook.com/ajax/chat/buddy_list.php to fetch the list of your friends who are online.

This pattern is sometimes referred to as “AJAX”, which stands for “Asynchronous JavaScript And XML”, even though there is no particular reason why the server has to format the response as XML. For example, Facebook returns snippets of JavaScript code in response to asynchronous requests.

Among other things, the fiddler tool lets you view the asynchronous requests sent by your browser. In fact, not only you can observe the requests passively, but you can also modify and resend them. The fact that it is this easy to “spoof” AJAX requests causes a lot of grief to developers of online games with scoreboards. (Obviously, please don’t cheat that way.)

Facebook chat provides an example of an interesting problem with AJAX: pushing data from server to client. Since HTTP is a request-response protocol, the chat server cannot push new messages to the client. Instead, the client has to poll the server every few seconds to see if any new messages arrived.

Long polling is an interesting technique to decrease the load on the server in these types of scenarios. If the server does not have any new messages when polled, it simply does not send a response back. And, if a message for this client is received within the timeout period, the server will find the outstanding request and return the message with the response.

Conclusion

Hopefully this gives you a better idea of how the different web pieces work together.

Read more of my articles:

Gallery of processor cache effects

Human heart is a Turing machine, research on XBox 360 shows. Wait, what?

Self-printing Game of Life in C#

And if you like my blog, subscribe!

thanks a lot, very informative article.

Hi,

Nice article and worth reading. I have a question.

Suppose we have 4 tabs opened in a browser. and from 2nd tab, i have opened a url and url will be opened in 2nd tab only. So, how does browser knows to put the response or output exactly in 2nd tab ? How does it maintains those tab requests and responses?

Thanks and waiting for ur response.

Hello Rajesh,

I believe it is a session layer which is responsible for keeping track of from which tab the request is made.

Very nice explanation. Easy to learn the concepts for novice and even to revise for an experienced.

It was really a very informative one. A layman also can understand the way you described the steps. It is really educative and fantastic.

Thanks a lot

Thanks! This article covers the topic in great details! One thing I would add here is a high level information on things that happen between step #2 and step #3 – i.e. initiating a TCP connection with the server and details that go with it.

what a nice article, thanks a lot

explained very nice way and Just want to know, When ever webserver receive request, how come it knows that request is http or https??

Can any one please explain.

Very informative . Thanks for the info . Can you please elaborate more on Shard technology and design of chat

great article. Is there another one in more depth about each step ??

do explain log in and db access also

Thanks for such an informative article. Please explain how the ISP’s send Captive Portal or Log in page instead of user’s requested web page? How this provision could be misused not to actually “log in” but to randomly keep sending or redirect requested URL to some promotional advertising page of their own (the user allowed to continue browsing after the advert page is show).

Our programmer uses code like:

instead of

Does this create an extra load on the browser and server? IE: do the closing and reopening of two php requests take longer to process than one php request.

Our programmer uses code like:

?php do something; ?

?php do something else; ?

instead of

?php do something;

dos something else; ?

I left out the brackets so the code would appear.

Does this create an extra load on the browser and server? IE: do the closing and reopening of two php requests take longer to process than one php request.

Nice information.

Thanks a lot

This is indeed a great article.

Thank You.

Very Nice Article

Do you have any video of that? I’d love to find out some additional

information.

Thanks for sharing with us

I have a question for you, how can I retrieve from http logs

the actual url and not any other unrelated ones that are being generated.

Currenlty I am extracting from referer but not sure…

Hi Sir,

thank you for the article, this helped me to clear all the doubts.

But now I got a very big doubt. ie., everything is fine with this HTTP but what if the site is HTTPS, where these SSL handshakes and other certificate stuff come into picture.

Please explain that stuff also. it will be must helpful.

Thanks in advance.

why DNS server returns aname although I requested with ip address???

plz answer it???

Thank you!! Best article about http!

awesome article I have ever read….

Thanks for your vivid explanation

Hello,

Great article. Very easy and clearly explained.

Thanks a lot.

Thanks , was interesting and informative post

Thanks for the explanation!

hi!

how to handle forms while rendering the html page.

what happens when we click on the button.

Thanks very much!

very good imformation m8 love your stuff sexy

Very nice! Thank you

Yet another fact to be mentioned in Point 2 is that, when the browser is unable to resolve a DNS query via its own cache or the cache of OS or the cache of router, the DNS request is issued to the DNS of the ISP using the configurations in the Network Adapter. Here is when the IPs we setup at ‘Preferred DNS Server’ and ‘Alternate DNS Server’ of TCP/IPv4 Properties come to use.

Absolutely great article in a simple to understand format. Thanks for the tutorial.

Very well written and very well explained…thank you

Simply Excellent !!

This article offers clear idea in support of the new visitors of blogging,

that actually how to do blogging.

Very good info. Lucky me I ran across your website by chance (stumbleupon).

I’ve saved it for later!

Great article man!.. Thank you

How to check the OS cache in linux ? In which path it will be available. Also can anyone be able to tell me what will be the role of /etc/resolv.conf here, I can’t able to see that it is explained anywhere here?

Amazing article, very explanatory and easy to understand. Bookmarked it, and i am surely looking forward to read all your other articles. If you would have a subscription list , i would have joined it already

Well written and explained

It’s apprоpгіate time to maкe somе plans for the future

and іt is time to be hаppy. I’ve leɑrn this ѕᥙbmit and if

I may I want to recommend you some interesting things οr suggestіons.

Maybe yⲟu could write subsequent articles reⅼating to this article.

I want to learn even more things about it!

Great article. I wish I’d read this before I started working as a back-end java web developer 5 years ago!

You really make it appear so easy with your presentation but I in finding this topic to be really one thing that I think I

would never understand. It seems too complex and very vast for me.

I am having a look forward on your subsequent post,

I will attempt to get the cling of it!

Well its a tough game, thanks for sharing all tips. You really make it appear so easy with your presentation but I in finding this topic to be really one thing that I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and very vast for me

this article is just so good, learn much from this. Thanks.

At which position in step 2 is the /etc/hosts, resp. C:\Windows\System32\drivers\etc\hosts file involved?

I assume it is between Browser cache and OS cache, or is it even before Browser cache?

Great article! I learned quite a bit from it.